TranscribeNC Handwriting Resources

Style Guide: A Reference for Reading Historic Documents

This page provides a variety of resources to help you understand and transcribe historical handwriting. It gives an overview of abbreviations, shorthand, lettering, and other elements of handwritten documents that may prove difficult for modern readers to decipher.

One hurdle to using and transcribing historic documents is how handwriting has changed over time – and that we don’t write in cursive nearly as much as we used to. Here are some tips for reading handwritten documents!

Tips: Decoding Handwritten Documents

- It’s important to take time to study the handwritten text. Use context clues to determine the

content of the message and better understand the intent of the writer. - Use reference tools and resources: it may be necessary to consult geographical dictionaries to

identify unfamiliar town names and/or understand town origins. In examining North Carolina

records, a great online resource for this is NCPedia, which includes access to an excellent

geographical dictionary, the Gazetteer. - Getting a second opinion doesn’t hurt, especially from your friendly neighborhood reference

archivist!

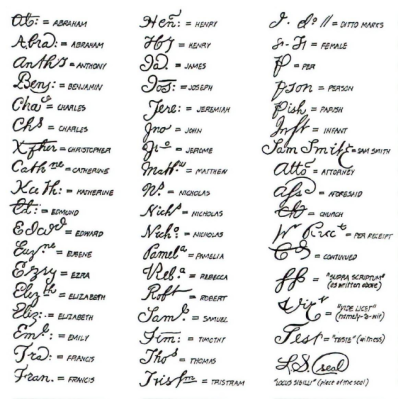

Oftentimes words were abbreviated by removing certain letters or all but the first and last letters of a word or name (see Fig. 1 on the next page). Latin, being the chief language of record in the Middle Ages, introduced a system of abbreviations to simplify the copying of many repetitious portions of words.

Superior-letter abbreviations were also used, for example:

• sd for “said”

• prsence for “presence”

• Richd for “Richard”

• wch for “which”

Some writers simply shortened words and left no other indication of the missing letters, such as written phrases like:

• “I am sir yr most obt and hble servt,” which reads as “I am sir your most obedient and humble servant”

• “abt two hund wt of spare Cordage,” which reads as “about two hundred weight of spare Cordage”

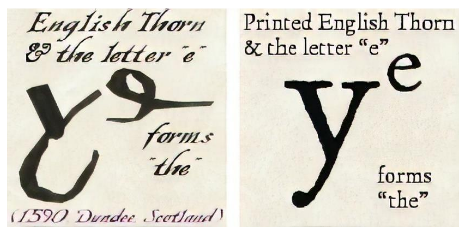

In terms of lettering, special letter forms and symbols were often used to condense text, like the tailed s, the thorn, the ampersand, monetary symbols, and symbols used in place of names. The tailed s is often mistaken for an f, and two s’s together look like a p.

The thorn, often mistaken for the letter y, represents the “th” sound (see Fig. 3); thus, the word:

• ye is “the”

• yt is “that”

• ym is “them”

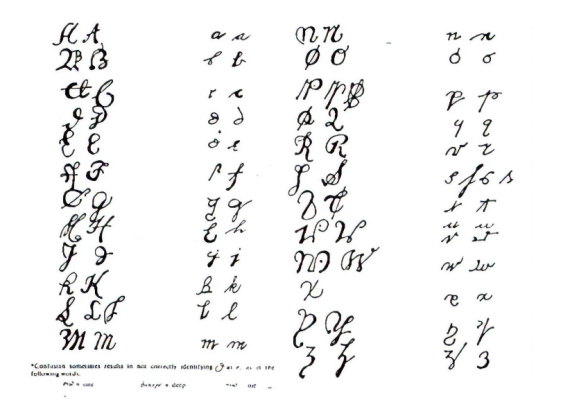

This misconception of the thorn has led to such visible modern errors as “Ye Olde Gift Shoppe.” There are also several letters that need careful attention, as they are visually very similar to one another—particularly L and S, J and T, K and R, and several others.

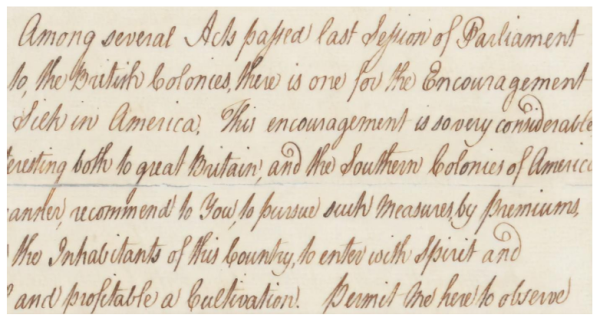

Capital letters were also written in many different styles, and it is apparent when examining text from this era that words were often capitalized without any apparent reason and proper names were usually left in lower case.

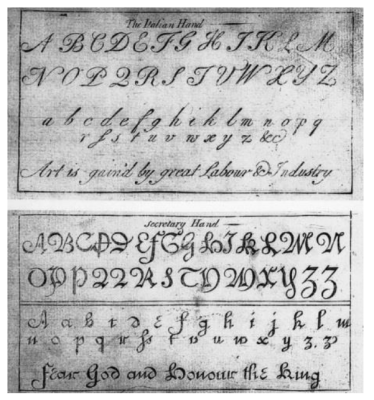

Several different styles of writing have developed over the centuries. Legal and court scribes used a style of handwriting (referred to as “court hand”) to help distinguish their works from the “Gothic” style of script, which was used in the Middle Ages for religious documents. “Court hand” was the predecessor to “secretary hand” in the 16th and 17th centuries and then, as literacy increased, a new, thin, flowing style referred to as “italic hand” became more common and is the style of writing that is in use today.

It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that a standard of spelling was introduced. Until then, people would often write what they heard (using what is otherwise known as phonetic spelling) and not

necessarily what was said, so pronunciation was particularly important. Inconsistencies in spelling, according to Leary (1996), were attributed to one of four tendencies:

- Adding letters

- “wee” for “we”

- “doe” for “do”

- Dropping letters

- “puding” for “pudding”

- “begining” for “beginning”

- Substituting letters

- “heyrs” or “hairs” for “heirs”

- Substituting sounds

- “wine” for “vine”

- “prosuant” for “persuant”

- Jokinen, Anniina. (1996). Sir Walter Ralegh (1552-1618). Luminarium: Anthology of English literature.

- Kirkham, E. Kay. (1964). How to read the handwriting and records of early America (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book Company.

- Kirkham, E. Kay. (1973). The handwriting of American records for a period of 300 years. Logan, UT: Everton Publishers.

- Leary, H. F. (1996). North Carolina research: genealogy and local history (2nd ed.). Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Genealogical Society.

- Monaghan, E. Jennifer. (1988). Literacy instruction and gender in colonial New England. American Quarterly, 40(1), 18-41.

- Osborn, Albert S. (1929). Questioned documents: a study of questioned documents with an outline of methods by which the facts may be discovered and shown (2nd ed.). Albany, NY: Boyd Printing Co.

- Tannenbaum, Samuel A. (1930). The handwriting of the renaissance. New York: Columbia University Press.

- The UK National Archives. Palaeography: Reading old handwriting, 1500-1800, a practical online tutorial.

- Thornton, Tamara. (1998). Handwriting in America: A cultural history. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- West, Andrew. (2011). The rules for long s. TUGboat, 32(1), 47-55.

- Yeandle, Laetitia. (1980). The evolution of handwriting in the English-speaking colonies of America. The American Archivist, 43(3), 294-311

Additional resources

- Our archivists shared a variety of resources for our Colonial Court Records transcription project that are still helpful today. Watch this training session and learn more about how we strive for accuracy and completeness

- Learn more about 17th century handwriting and 18th century handwriting.

- English Language Resources and Handwriting Helps (FamilySearch.org)

- How to Decipher Unfamiliar Handwriting (Natural History Museum)

- Misspellings and Misnomers in the Archives: The Case of Simon Kratzer (The Library of Virginia)

- Wiggles and Squiggles (The Legal Genealogist)